For several years in a row, I’ve been updating calculations on the returns to beta in the Norwegian stock market. My latest calculations, now covering 23 years, only substantiate the conclusion: A higher beta is associated with lower returns. A lot lower.

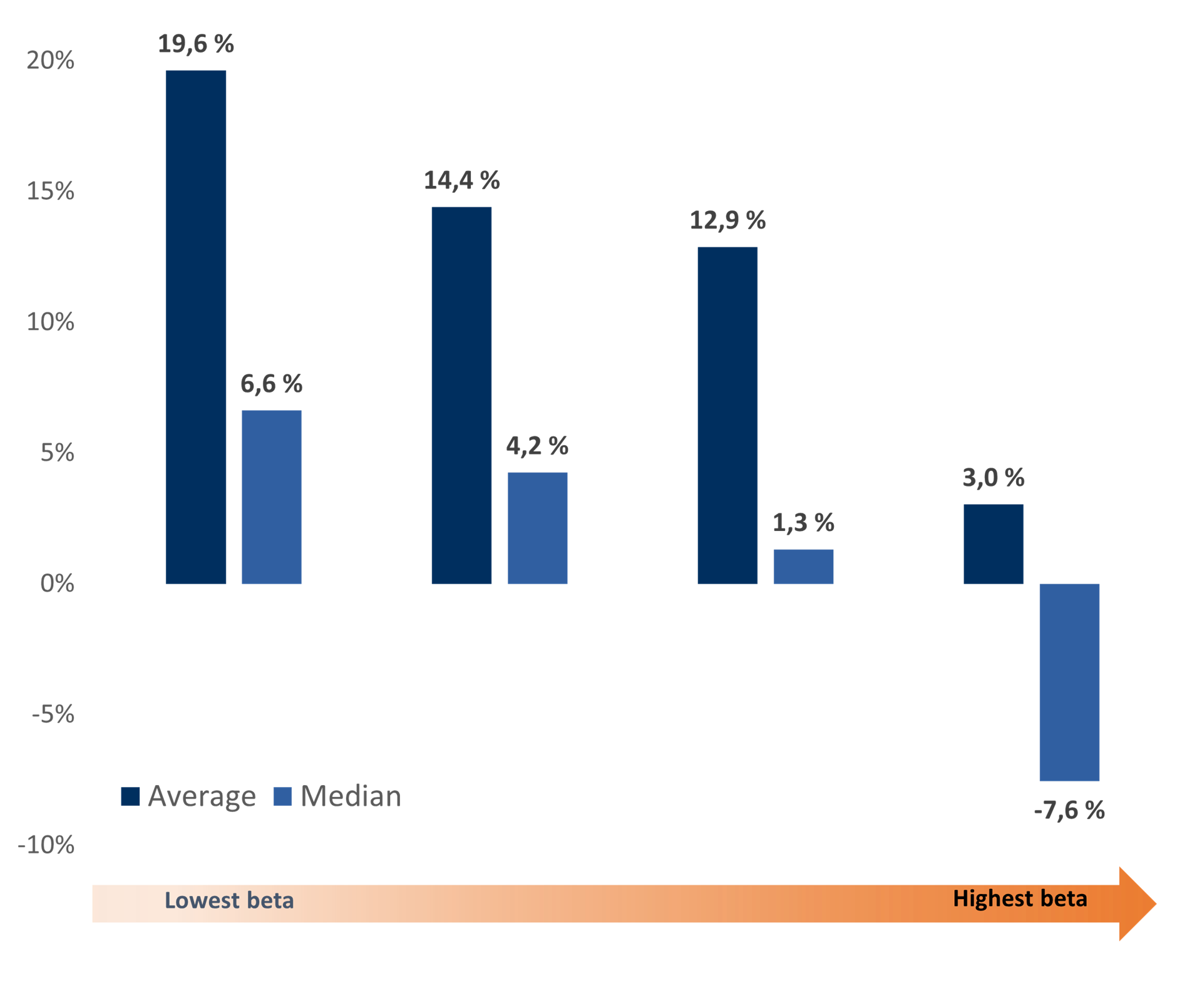

If, at the start of every year since 2001, you moved your portfolio into the quartile with the lowest beta calculated over the past year, you would have reaped a compound return of 19.6%. If instead you had chosen the top-beta quartile each year, your average return would have been a meager 3.0%. Compounded over 23 years, that’s a choice between almost 6,200% and 200%, which in hindsight is an easy choice.

Beta, of course, is a measure of systematic risk, or the way a stock fluctuates relative to the market. In modern portfolio theory, not so modern anymore, a higher beta is associated with higher expected returns. It does make sense; if you take on more risk, generally considered undesirable, you’d want to get something in return. In reality, well documented for a number of markets around the world, higher betas have delivered systematically lower returns.

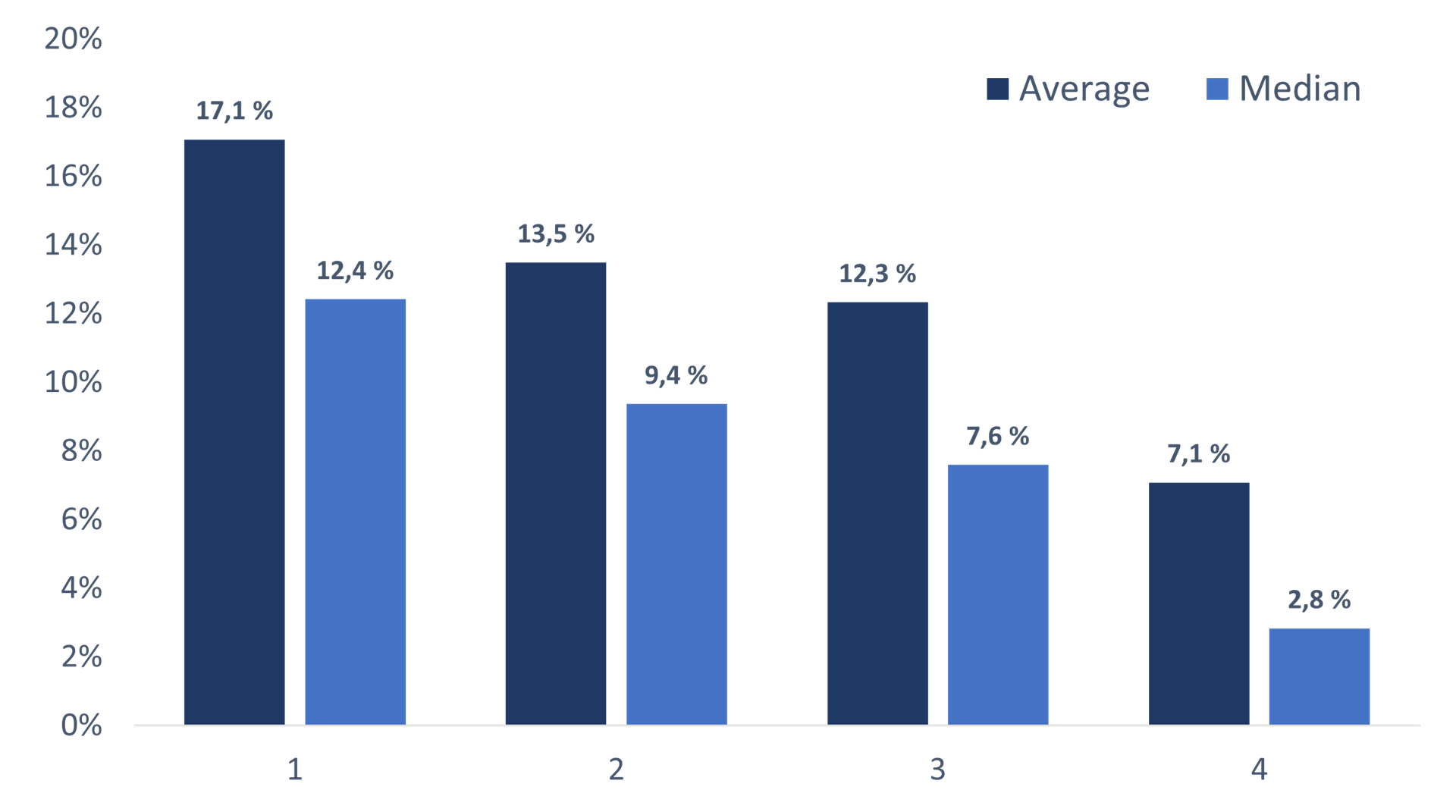

We now have confirmation that it applies to the Nordics too, as our summer intern Bjarne Aarsland made a similar exercise for stocks in the Nordic benchmark index VINX. His data are from Bloomberg and thus calculated in a slightly different manner (they also include one more year), but the conclusion is strikingly similar: Here, too, a higher beta is associated with lower returns – and monotonically so, meaning that for every quartile of increasing beta, compound return is lower. From 17.1% for the lowest-beta quartile to 7.1% for the highest-beta quartile.

Expensive excitement

Expensive excitement in the Nordics

There is no dearth of international studies with similar conclusions. In academic research, “betting against beta” has become an epithet for work demonstrating the negative returns to beta, typically by shorting high-beta stocks and going long low-beta stocks. A standard part of the explanation has been an investor preference for lottery-like stocks. Our calculations, though, imply that there is more to this than just lottery-stock preferences, given the monotonically falling returns to beta. Lottery stocks are most likely to be found in the fourth quartile.

Research has shed some more light on this phenomenon. It is more pronounced for small stocks, it reflects better returns for quality stocks, it gets stronger when economic uncertainty is low or volatility increases (they don’t all agree), and it is all about the individual companies, not industry-level betas.

Either way, systematic risk seems to be overbought. Whereas time in the market is convincingly more important than timing the market, and certainly more foolproof, you can’t enhance your market returns by loading up on market risk. If you want higher returns, you need to pick the right securities.