It is tempting to view the operation of a national treasury as a brilliant business scheme: You set your own prices (tax levels), payment is mandatory, and you even get to decide how many goods will be supplied in return – and of what quality. No wonder being king used to be so popular. If you can, just ask the spirit of Louis XIV of France, the “Sun King”.

Today, this setup works poorly. Chieftains dependent on popular support may find more indirect ways to get rich – let’s call it nepocracy – but the money flows out of the treasury when you have to buy customer satisfaction. In short: you have to borrow instead.

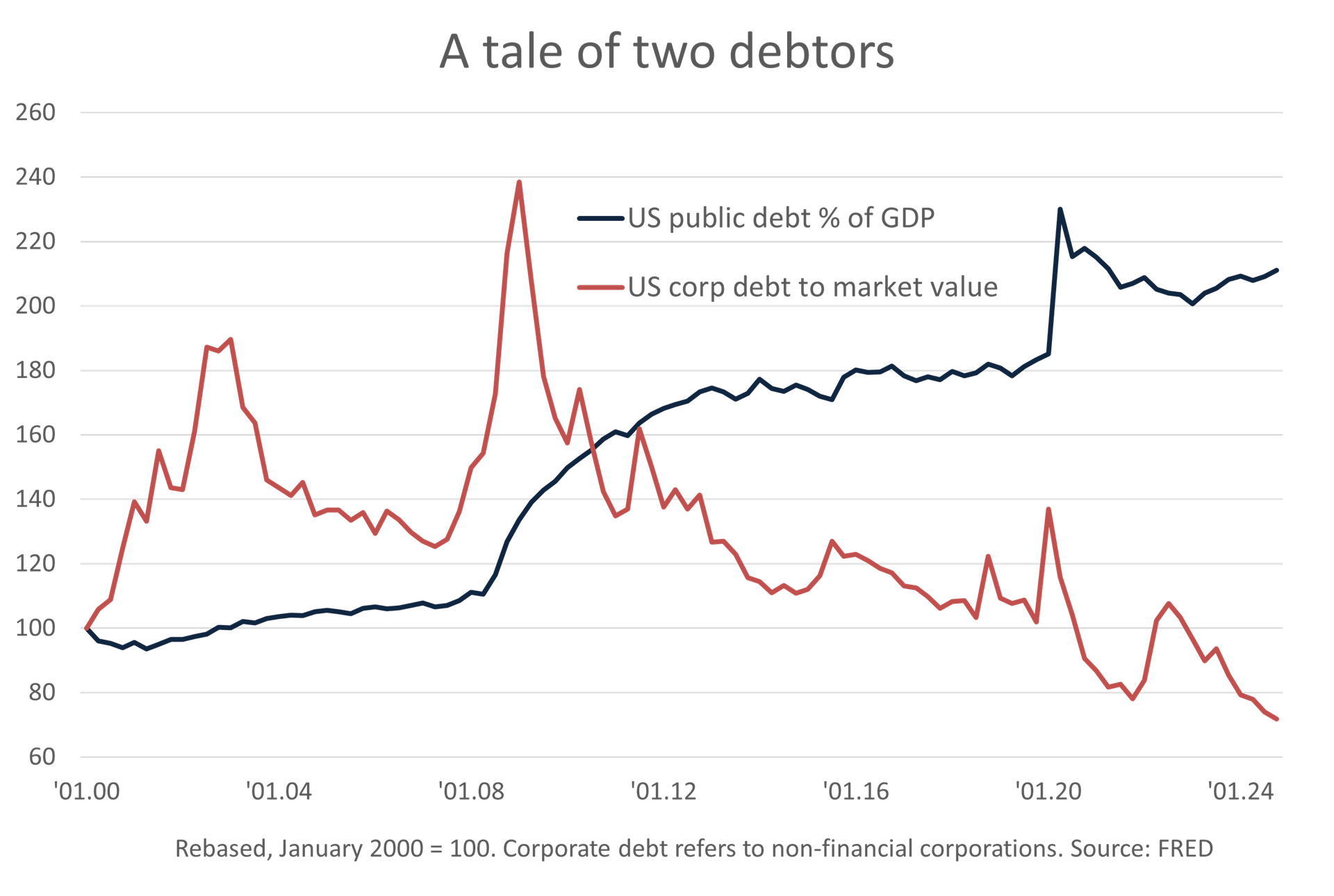

In the US, there has been a lot of borrowing. Government debt has grown from 65 per cent of GDP in 2007 to over 120 per cent today. The dollar’s role as a reserve currency has made it possible to borrow ever-increasing amounts without interest rates shooting through the roof, but it’s not sustainable. This is an important backdrop for the many, shall we say, incomprehensible initiatives from President Trump. It also adds a vulnerability to the dollar that used to be less evident.

At first glance, private companies appear to face a tougher challenge: They can never stop striving to supply the best possible products at the lowest possible cost, and losers are continuously eliminated. This cutthroat competition, however, has produced more robust business models – and much more prudent handling of debt.

If we again measure debt as a percentage of GDP, US non-financial corporations have only seen a moderate increase since the start of the millennium – and since 2020, the level has fallen from 56 to 48 per cent of GDP. Furthermore, the average debt/equity ratio has been stable or slightly falling ever since the Great Financial Crisis. And using the market value of equity instead of the book value, the equity ratio has risen to as much as 75 per cent. You won’t find this figure in the swarm of debt-concern headlines.

To the extent that US policy is steering the economy towards recession – it’s certainly not helping at the moment – do note that the business sector is much better equipped than the public sector. It’s also in better shape than it has been for many years.

The same applies in the UK, where government debt has exceeded 100 per cent of GDP. In contrast, corporate equity ratios have risen from below 50 per cent after the financial crisis to more than 70 per cent now. And that’s using book equity.

I haven’t found figures for the eurozone debt ratio. But while public debt has grown from less than 70 per cent of GDP in 2008 to almost 90 per cent today, the non-financial corporate sector has kept its debt ratio fairly stable at around 75 per cent. Over the past four years, it has shown a clear downward trend.

If these figures don’t lift the weight off your shoulders, they should at least remind you that there are more well-run companies than governments. It’s the former that we invest in.