Last week, Governor Ida Wolden Bache delivered her annual address. She spent much of the speech emphasising the importance of a credible monetary policy but also devoted a short paragraph to interest rate differentials.

I would be happy to add a few more paragraphs. As a starting point, let’s note that the NOK has weakened significantly over several years. Since 2013, the nominal effective NOK exchange rate has fallen by more than 30 per cent, and adjusting for inflation differentials makes little difference: The real effective NOK exchange rate has depreciated by almost 25 per cent. You don’t need statistics from the IMF to see that this is way out of the ordinary.

A weak NOK makes imports more expensive and exports cheaper, and improves profitability in the traded goods’ sectors of the economy. If this leads to high wage increases in these sectors which then spill over to the sheltered sector, there will be a further boost to inflation. No wonder she stated that «the krone depreciation made monetary policy trade-offs more demanding last year».

During the years of a steadily weaker krone, interest rate differentials against other countries went from positive to negative. In the annual address, key policy rates are used to illustrate this point. If we are to say something about the currency market, we better use market rates. Here I will use one-year rates, but rest assured that two-year rates bring about exactly the same conclusions. And since we don’t trade yield curves, I use US interest rates. As interest rates go, we follow the US more closely than e.g. Sweden does.

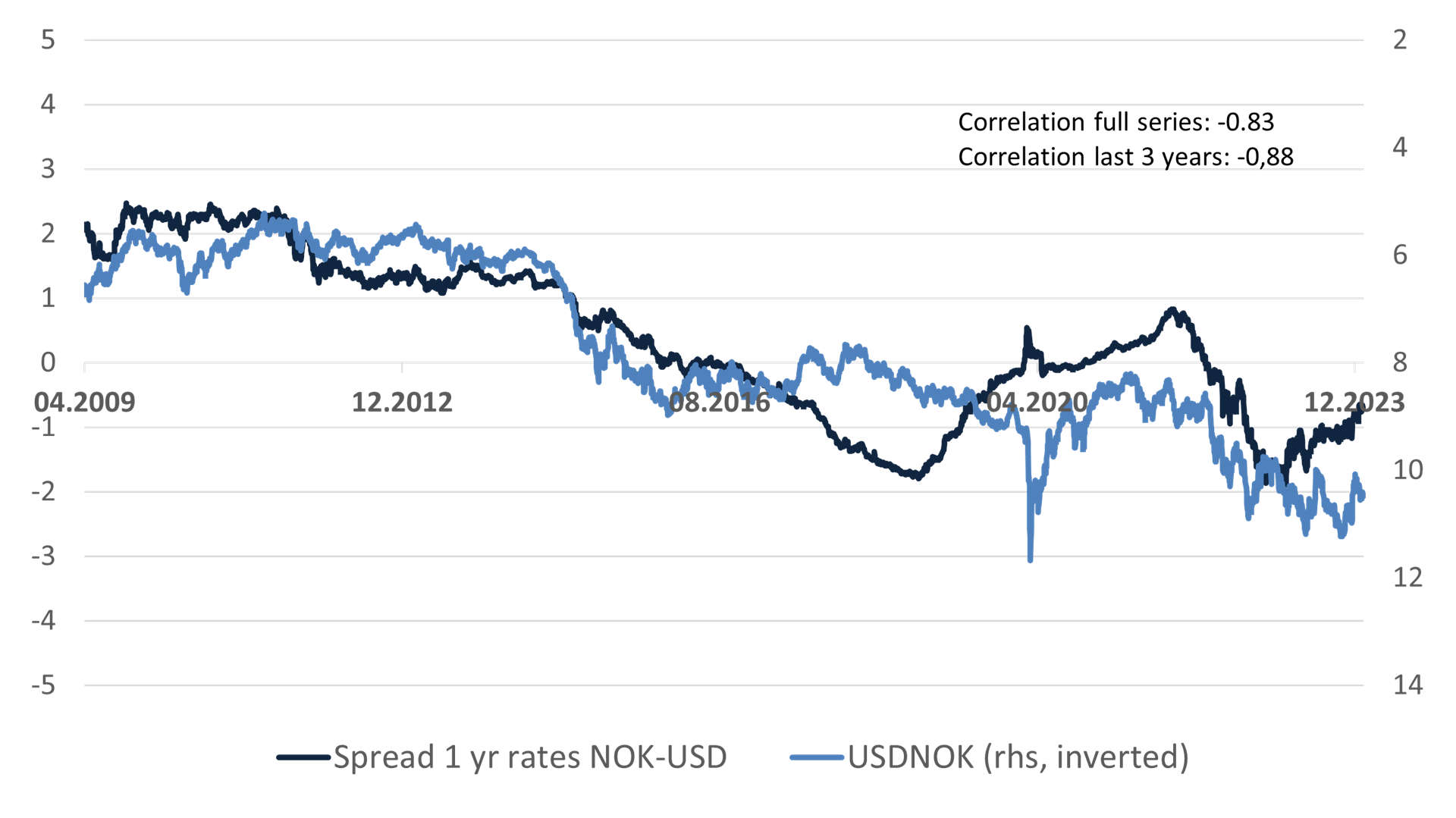

The interest rate differential spiked during the financial crisis. It was more or less stabilised after the first quarter of 2009, so I'll start there and follow the figures up to the end of January this year. And guess what: There is a correlation of -0.83 between the interest rate differential and the USDNOK exchange rate. In other words, the international value of the Norwegian currency typically rises (the USDNOK falls) when the interest rate differential increases.

I use long series for better explanatory power, but I may add that the correlation for the last three years is -0.88. We can easily see this from the graph.

In all probability, the causal direction goes from the interest rate differential to the exchange rate, not the other way around. A simple regression analysis then reveals that the interest rate differential explains almost 70 per cent of the variation in the exchange rate. The effect is highly significant.

We don’t gain much by throwing in the oil price, which used to be regarded as an important cause of fluctuations in the NOK rate. Statistically speaking, the oil price is redundant.

We are left with the interest rate differential against other countries. When it is falling, the NOK tends to depreciate. This illustrates a well-known exchange rate puzzle: In theory, higher interest rates should be matched by a weaker exchange rate, or at least expectations thereof. In practice, the exchange rate tends to rise if interest rates are kept higher. A positive carry attracts capital.

For small currency areas like Norway, the critical line may in fact be some distance above zero. Presently, however, Norwegian interest rates are indeed lower. This applies to both market rates, which I have used, and key policy rates, which the central bank governor illustrates in her annual speech – and can do something about.

Economists are currently competing to estimate when we will see the first interest rate cut and how quickly interest rates will continue to fall. The question is whether they should focus on Governor Ida Wolden Bache. For the time being, they should probably shift their gaze to US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. She won't cut rates before he does.