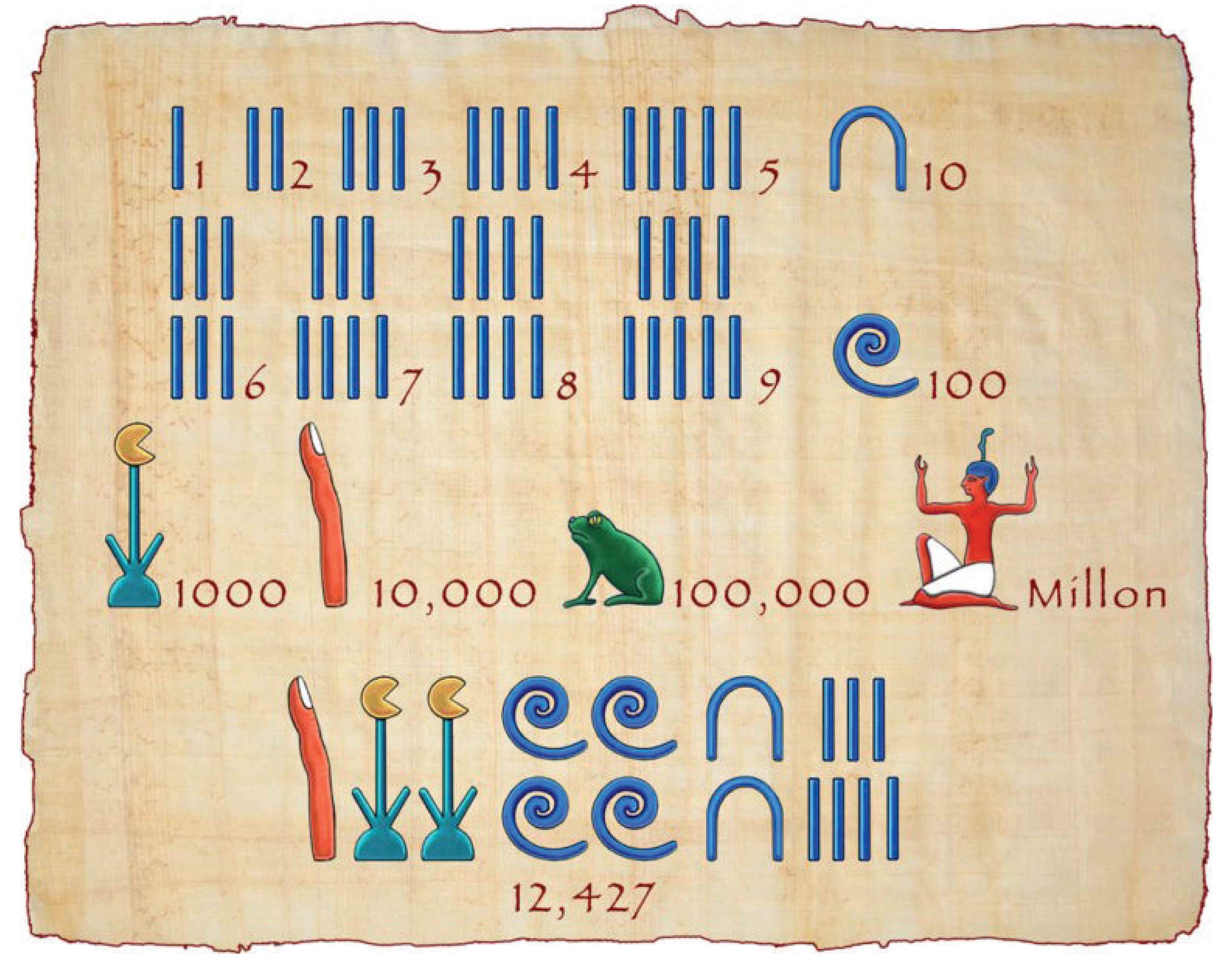

Count like an Egyptian

Having each year begin with January is really just the result of a historical coincidence. So too are financial records.

Having each year begin with January is really just the result of a historical coincidence. So too are financial records.

January hasn’t always been the first month of the year. It owes its prominence to an uprising against the Romans in Hispania (present-day Spain and Portugal) in 153 BCE. Up until then, the Roman calendar year began on 1 March, while new consuls traditionally took office in mid-March. Due to the severity of the conflict, the consular transition was moved to 1 January. Over time, the calendar year followed suit.

In finance, we are obsessed with measuring annual returns. While companies may have deviating financial years, asset managers abide by the calendar. Over the past 30 years, for instance, records will show that the MSCI World Index returned almost 30% in 2013, while it lost 38% in 2008. Measured over annual returns, the standard deviation was 17%.

If we’d counted years like they did in the old Roman republic, financial history would look a lot scarier. Losses in 2008 would increase to 42%, but a large part would be recouped through the following year’s 47% return. Volatility would rise to almost 19%.

There have in fact been many different calendars. The Celts could have celebrated New Year’s Eve around present-day Halloween, marking the end of the harvest and the start of the darker half of the year. Ancient Egyptians had the new year commence around the second half of July, when the heliacal rising of the star Sirius tended to signal the annual flooding of the Nile.

If we imagine Egyptian calendars ending on 31 July, we get totally different financial records. The year ending on 31 July 2008 would show a modest decline of 14%, while the following year would deliver a loss of 19%. Mind you, that’s just five months after the old Roman counting reported a 42% loss. And, still counting like the ancient Egyptians, volatility would fall to 14.6%.

Simply put, using a different calendar, the stock market would look like a totally different creature. So there is an element of random walk even in the way we measure financial returns. Good thing they are skewed to the upside.

About the author