Last week, Governor Ida Wolden Bache delivered her annual address. She spent much of the speech emphasising the importance of a credible monetary policy but also devoted a short paragraph to interest rate differentials.

I would be happy to add a few more paragraphs. As a starting point, let’s note that the NOK has weakened significantly over several years. Since 2013, the nominal effective NOK exchange rate has fallen by more than 30 per cent, and adjusting for inflation differentials makes little difference: The real effective NOK exchange rate has depreciated by almost 25 per cent. You don’t need statistics from the IMF to see that this is way out of the ordinary.

A weak NOK makes imports more expensive and exports cheaper, and improves profitability in the traded goods’ sectors of the economy. If this leads to high wage increases in these sectors which then spill over to the sheltered sector, there will be a further boost to inflation. No wonder she stated that «the krone depreciation made monetary policy trade-offs more demanding last year».

During the years of a steadily weaker krone, interest rate differentials against other countries went from positive to negative. In the annual address, key policy rates are used to illustrate this point. If we are to say something about the currency market, we better use market rates. Here I will use one-year rates, but rest assured that two-year rates bring about exactly the same conclusions. And since we don’t trade yield curves, I use US interest rates. As interest rates go, we follow the US more closely than e.g. Sweden does.

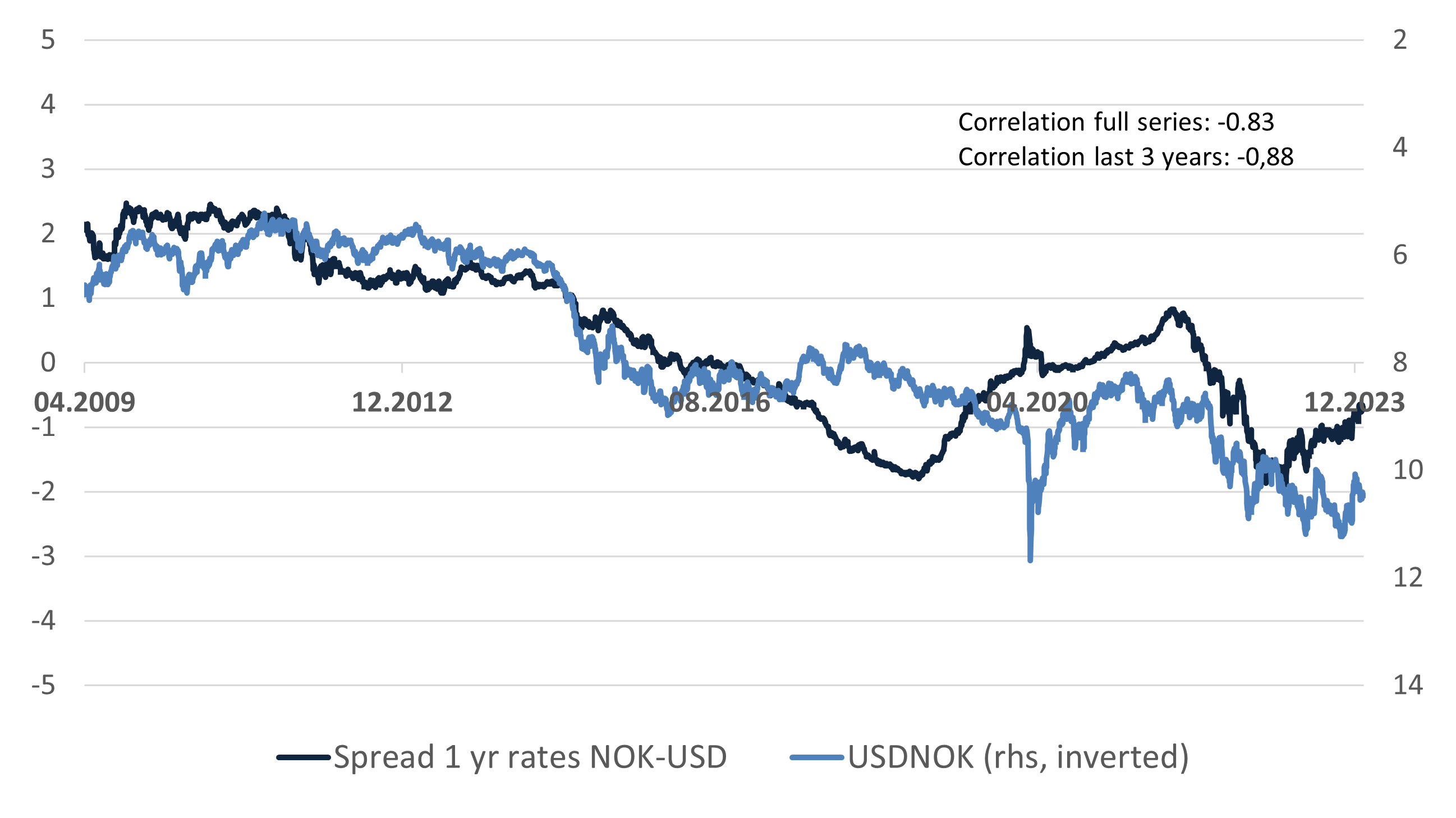

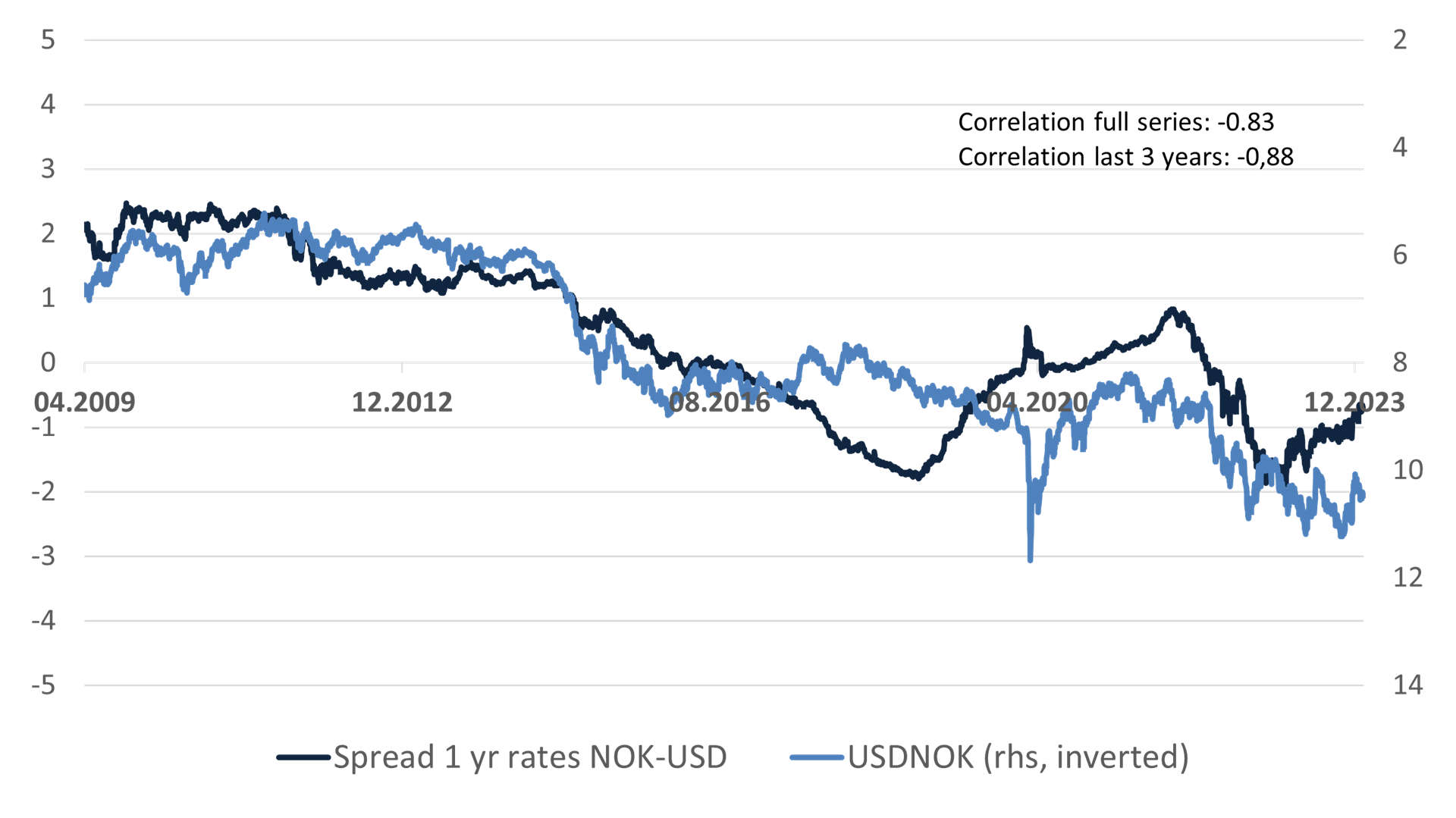

The interest rate differential spiked during the financial crisis. It was more or less stabilised after the first quarter of 2009, so I'll start there and follow the figures up to the end of January this year. And guess what: There is a correlation of -0.83 between the interest rate differential and the USDNOK exchange rate. In other words, the international value of the Norwegian currency typically rises (the USDNOK falls) when the interest rate differential increases.

I use long series for better explanatory power, but I may add that the correlation for the last three years is -0.88. We can easily see this from the graph.

In all probability, the causal direction goes from the interest rate differential to the exchange rate, not the other way around. A simple regression analysis then reveals that the interest rate differential explains almost 70 per cent of the variation in the exchange rate. The effect is highly significant.

We don’t gain much by throwing in the oil price, which used to be regarded as an important cause of fluctuations in the NOK rate. Statistically speaking, the oil price is redundant.

We are left with the interest rate differential against other countries. When it is falling, the NOK tends to depreciate. This illustrates a well-known exchange rate puzzle: In theory, higher interest rates should be matched by a weaker exchange rate, or at least expectations thereof. In practice, the exchange rate tends to rise if interest rates are kept higher. A positive carry attracts capital.

For small currency areas like Norway, the critical line may in fact be some distance above zero. Presently, however, Norwegian interest rates are indeed lower. This applies to both market rates, which I have used, and key policy rates, which the central bank governor illustrates in her annual speech – and can do something about.

Economists are currently competing to estimate when we will see the first interest rate cut and how quickly interest rates will continue to fall. The question is whether they should focus on Governor Ida Wolden Bache. For the time being, they should probably shift their gaze to US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. She won't cut rates before he does.

Capital flows affect stock prices. This basic proposition aligns poorly with conventional wisdom in finance. It’s also easy to dismiss – after all, for every buyer there is a seller, right? Duh!

As it happens, though, this is the subject of a growing number of interesting research efforts. They revolve around the perhaps somewhat nebulous concept of stock market elasticity.

In basic economics, we talk about price elasticity. If a price rise of 1% lowers the volume of goods sold by 5%, demand is highly elastic – meaning it is very sensitive to changes in price.

In finance, the concept is somehow turned on its head: We want to know the sensitivity of the stock price to changes in capital invested in the stock market through mutual funds, pension funds etc. If the market is elastic, it can absorb this supply of capital without really changing the price. Given a price elasticity of 5 (or, conversely, a multiplier of just 0.2), an inflow of 5% would only increase the price level by 1%.

In standard models, the market is even more elastic. When prices rise, more investors find stocks expensive, and decide to sell. We’re taught that stock market returns are a function of the risk-free rate and a perhaps inexplicably high risk premium. Capital flows don’t enter into it. There’s perfect competition and a given price in a perfect market.

Not so in real life.

This acute insight has started to make inroads into financial research too. Here’s the crux: What if investors don’t find the new price level expensive? What if they actually don’t care about the price?

This is the case for investors with a fixed mandate, most notably passive investors like index funds. If they have an inflow of a billion dollars, this capital must be invested in the index. If that makes prices rise, so be it.

And they certainly do. According to research now gaining traction in the financial community, the stock market is highly inelastic: 1 dollar invested in the stock market makes the aggregate market value rise by as much as 5 dollars (a multiplier of 5). The rising share of passive investment means that fewer investors now find the new price level too high. There are simply more investors for whom the price level is irrelevant.

See the implications?

- Passive investment contributes to stocks being permanently higher priced. Pundits have claimed for years that the market is overvalued. It just might stay that way.

- This applies primarily to index stocks, which explains why many active investors have struggled over the past 15 or so years. Large fund flows into passive funds have pushed up the prices of index stocks.

- Several papers, like this one, find that the effect is disproportionately more powerful for larger stocks; their price appreciation is not corrected by active investors. This then explains the growing concentration in a small number of index stocks like “the Magnificent Seven”.

- It also makes it easier for retail traders to move prices in smaller stocks. Remember the GameStop frenzy, where Reddit users contributed to pushing up the price from $17.25 to roughly $500 in January 2021? One important reason, apparently, was that over 60% of the company’s shares were held by perfectly inelastic (passive) investors.

I dare say it’s getting harder and harder to explain why conventional wisdom fails to explain such features of the stock market.

About the author

Finn Øystein Bergh

Chief economist and -strategistFinn Øystein Bergh joined Pareto in 2010, the first years in Pareto AS before joining Pareto Asset Management in 2015. He has previous experience as a journalist, chief economist and later managing editor in the financial magazine Kapital. Finn Øystein Bergh holds an MSc in Economics and Business Administration, MBA, cand. polit. (an extended master's degree) in political science and cand.polit. in economics. He writes the financial blog Paretos optimale, and has published several books on economics.